More information

General Context I.

The Roman Empire (Imperium Romanum) came into being as a result of a long process of development, but in reality, it was the genius of Emperor Augustus (31 BC – 14 AD) that brought it to life. With this introductory thought, we are essentially describing a significant turning point in the history of Europe — and perhaps the world.

Rome, a small settlement founded during the Iron Age (according to legend, in 753 BC), first grew into a city, then fought both its internal and external battles in order to exchange the cloak of monarchy for the toga of the republic and consuls’ rule. Eventually, almost as if by magic, it awoke as an empire spanning half a continent, a state that cried out for reform. During the prolonged crisis, a bloody civil war broke out that dragged on for decades, from which Julius Caesar’s adopted son, Octavian rescued the Republic. His economic, military, and above all, administrative reforms set the course for Roman development for centuries, and quickly led to a state that extended its power from the Scottish Highlands to Jerusalem, from Morocco to the Carpathians.

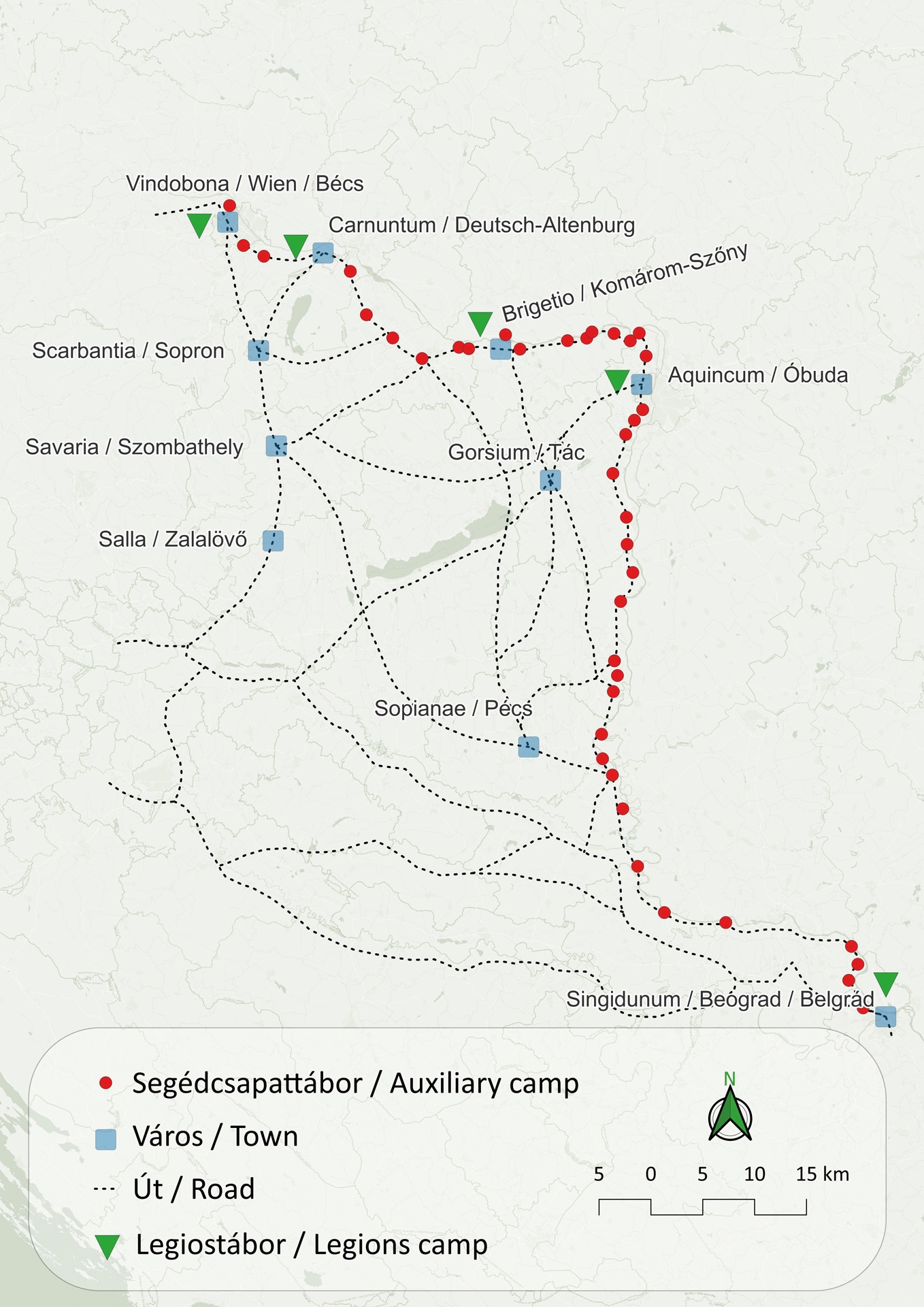

The largest unit in the Roman army (5,500–6,000 men) was the legio, pronounced with a short “e” and “o”. Alongside the legions served auxiliary forces, known as auxilia. These came in two main types: the cohors (cohort) was the name for an infantry auxiliary unit (500 men), while the ala referred to a cavalry unit.

By the time of Augustus, we can speak of a true professional army, in which freeborn men served for 20–25 years, depending on the unit. A basic rule was that only Roman citizens could be enlisted in the legions. And here, a brief digression is necessary, because the Roman Empire truly functioned as an empire — that is, everyday life was regulated by strict laws, and these naturally extended to the military.

General Context II.

In many respects, the Empire differed from modern states, and one of the most fundamental differences lay in the legal status of the population. As a state with a city-state past, the Empire long regarded those not born in Rome or not belonging to a Roman gens (clan) as second-class, non-full citizens. As Rome gradually conquered the Italian Peninsula, it was extended to the newly conquered areas. It would only be centuries later that the moment would come when all freeborn men in the Empire were granted citizenship.

Thus, only such men could serve in the legions, and holding Roman citizenship was also a prerequisite for advancement in state or administrative positions. Roman society was divided into various classes, between which social mobility was difficult. Beneath the senatorial elite stood the equestrian order, who also held leadership roles in the empire, and below them were the common citizens — the plebs. Sons of the elite classes began their careers as legion officers, climbing the ranks so that they could later, as mature men, participate in governing the Empire.

The auxiliary system worked differently. Here, men without Roman citizenship could join (in extreme cases, through forced conscription), and after 25 years of service they were not only granted Roman citizenship but also given land suitable for farming in the conquered provinces. These auxiliary soldiers most often chose to settle near their place of service and almost exclusively married local-born women.

Conquest was, so to speak, a natural part of the system. And roughly at the point when the great wars of expansion came to an end, a slow decline began — one that lasted for centuries and was further aggravated by external factors.

The Conquest of Pannonia I.

In addition to encompassing the entire territory of today’s Transdanubia (western region of Hungary), the Roman province of Pannonia also included small parts of present-day Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Austria, and Slovakia. From a military aspect it was one of the most important provinces of the Roman Empire. Its name was likely derived from the name of the Pannonian (Pannonius) people. Scholars have long debated which ancient ethnic group they might be identified with, but until the 2010s, these attempts were largely unproductive. Based on excavations at Regöly by Géza Szabó and Mária Fekete, it is now highly probable that the foundations of the later Pannonians were laid by a people who migrated from the East in the 7th century BC.

However, the uncertainty surrounding this identification is increased by the significant chronological gap between these early settlers and the Roman conquest of the province. Interestingly, though, some place names persisted stubbornly even in the language of the conquerors. For example, the Latin name of the Rába River, Ar(r)abo, can still be recognized in the river’s current name.

Hungarian archaeology regards the Iron Age as the final phase of prehistory. By the end of this period — approximately between 550/500 BC and 8/11 AD — the region of Transdanubia was primarily dominated by Celtic and Illyrian or Pannonian groups. As far as the archaeological evidence suggests, the Romans were generally uninterested in Celtic territories unless their own interests were threatened.

In this context, the first step on the road to conquering the province is usually considered to be the failed military campaigns aimed at securing the hinterland of Aquileia, founded in 181 BC. These campaigns aimed to capture Siscia (in 156 BC and 119 BC. After these failures, the region largely fell out of Roman interest for a long time, only to regain attention in 35 BC, when the Romans finally succeeded in capturing this strategically crucial settlement. This not only opened up the vast territory between the Drava and Sava rivers and the navigable Sava Valley, but also provided an ideal route for advancing toward the Balkans.

Following several decades of minor and major armed conflicts and uprisings, in 11 BC the future emperor Tiberius “pacified” the region, and a new province was established under the name Illyricum. The fact that the local population did not easily accept Roman rule is evident from the continued uprisings, which dragged on until 8 BC — and even in 6 AD, they set fire to the Roman army’s hinterland as it marched (beyond the Danube).

The Conquest of Pannonia II.

In the ensuing centuries, the province’s history remained marked by military events. During the reign of Emperor Domitian (81–96 AD), unrest stirs among the Germanic tribes living north of the province, prompting an increase in the number of auxiliary troops stationed there. This growing tension was due to the slow migration of Gothic tribes, who by the mid-2nd century had reached the northeastern fringes of the Carpathian Basin. Meanwhile, the Legio II Adiutrix, stationed in Aquincum, had been redeployed to the Parthian War, significantly weakening the province’s defense. As a result of these population movements, the Lombards crossed the Danube in 166–167 AD, marking the beginning of the so-called Marcomannic Wars, which lasted until the death of Emperor Marcus Aurelius in 180 AD.

The extent of the devastation is difficult to depict, but the events led to fundamental changes in the life of the empire. On the one hand, reconstruction of the military camps along the limes (border fortifications) began, with many new watchtowers built—particularly under Commodus. On the other hand, a major governmental crisis unfolded, which persisted until 193 AD. In that year, the legions stationed in Pannonia declared Septimius Severus emperor at Carnuntum. After the second Parthian War, Severus returned to the province and in 202 AD toured the limes: he set out from Singidunum on March 8 to arrive in Carnuntum by April 9 to celebrate the anniversary of his proclamation as emperor. During this time, significant road reconstruction also took place near Arrabona.

Following the reign of Severus, a new wave of construction began under Emperor Caracalla (211 –217 AD), perhaps not unrelated to the imperial visit of 214 AD.

The Conquest of Pannonia III.

The significance of these construction projects is reflected in the fact that over the following century, essentially no further building activity took place along the limes. Although the third century was marked by frequent conflicts, the Pannonian border remained one of the most heavily fortified sections of the Empire.

The next major phase of construction occurred after these troubled decades, during the reign of Diocletian (284–305 AD). A new type of watchtower emerged as a result, and many forts were renovated along with their access roads; even new strongholds were established. Witnessing the collapse of the linear frontier defense system during the third century, the emperor committed himself to fundamental reforms. A new defense force was created: a mobile, fast-reacting cavalry army for deep operation.

Unfortunately, we know very little about troop movements in the fourth century, as the practice of erecting inscriptions gradually declined. What can be stated with certainty is that during the reign of Constantine the Great (307–337 AD), many buildings along the limes were renovated, and new ones were constructed as well. It is likely that the Csörsz Ditch was also established at this time, and for these reasons.

The last major building phase along the limes began under Constantius II and was completed under Valentinian I (364–375 AD). The latter ordered the renovation of numerous castella (fortified outposts) and the construction of new watchtowers adapted to the terrain.

The decades that followed marked a period of gradual decline. After 395 AD, the payment of military wages ceased, and by the 420s, Roman currency circulation had come to end. By the mid-fifth century, this effectively meant the dissolution of the limes system, and Roman troops yielded control of the provinces to newly arriving settlers.

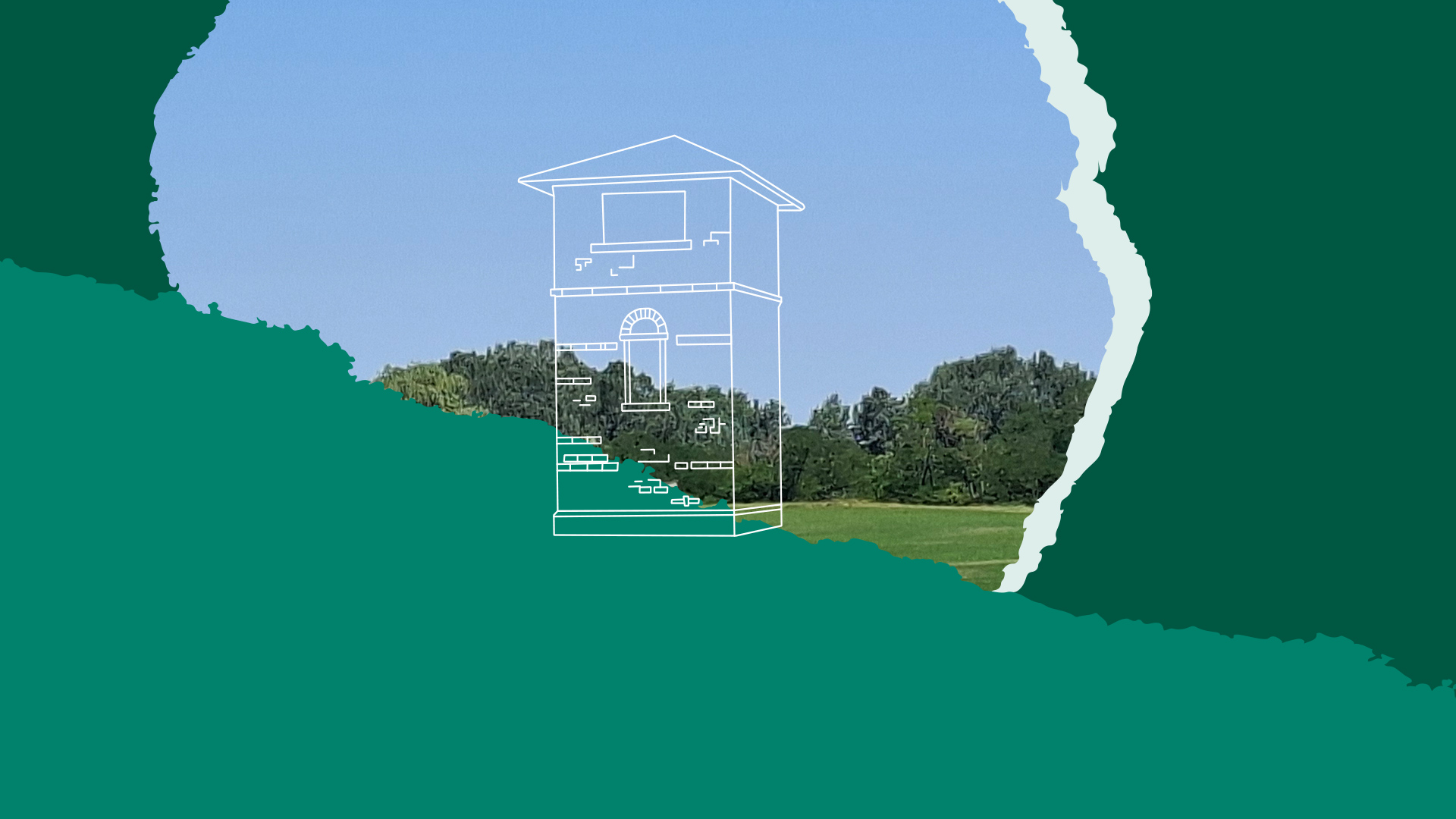

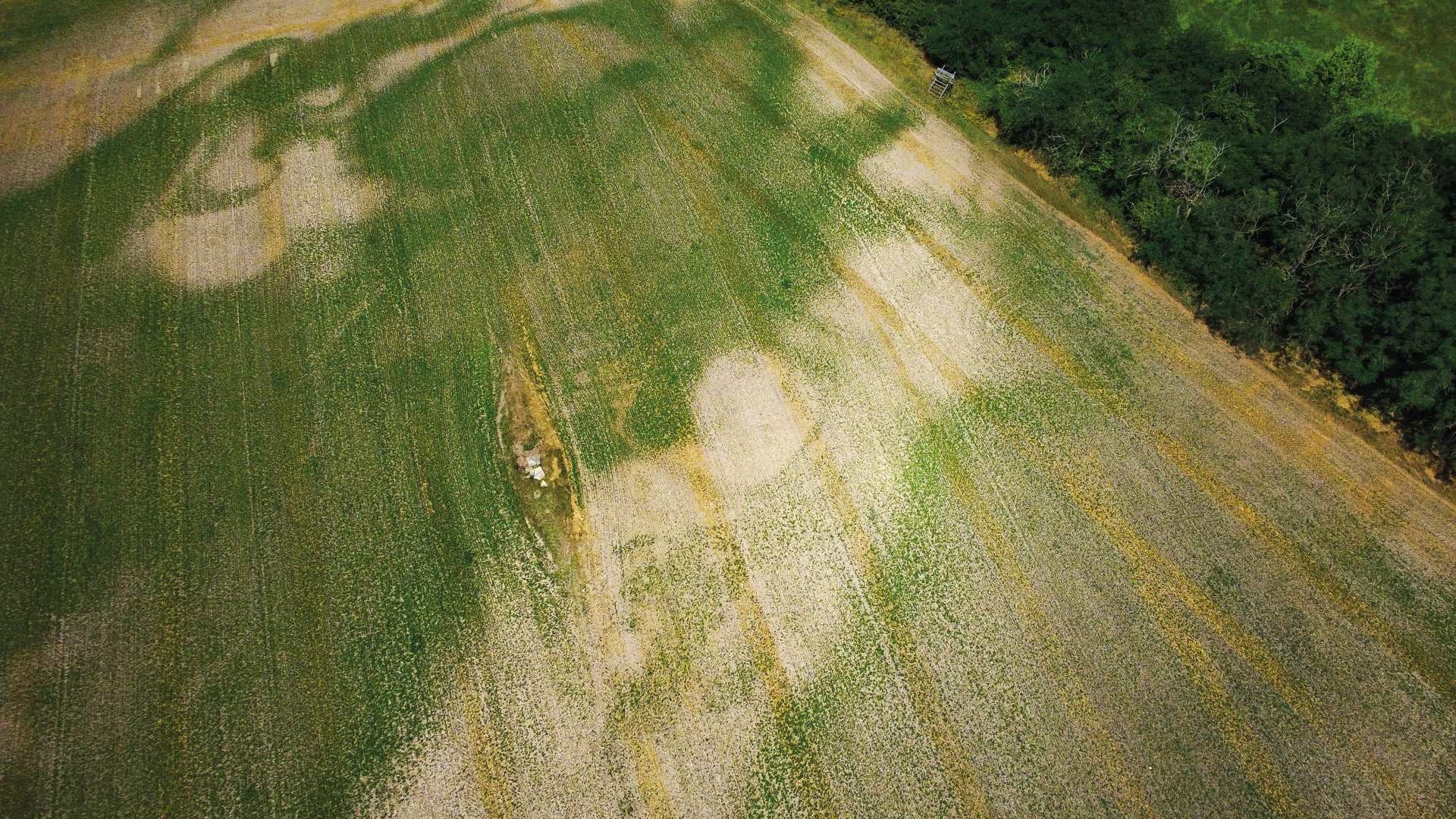

Watchtower near Nagyszentjános

To date, archaeological research has identified two watchtowers within the territory of the settlement: one at the western, and one at the eastern boundary of the administrative area. In the area known as Proletár Field Eszter T. Szőnyi successfully excavated a 15-by-15-meter stone tower, surrounded by a ditch 2 meters wide and 1.4 meters deep, with boundary dimensions of 23 by 27 meters.

Alongside the tower, she also discovered bread ovens datable to various periods, strongly suggesting that the soldiers stationed there managed their food supply on site. The tower itself can only be broadly dated to the 2nd–3rd centuries.

Pannonia régészeti kézikönyve. Eds.: Mócsy András – Fitz Jenő, Akadémiai kiadó Bp. 1990.

Visy Zsolt (Ed.): Rómaiak a Dunánál. A Ripa Pannonica Magyarországon, mint világörökségi helyszín, Pécs, PTE Régészet Tanszék 2011.

Szabó Géza – Fekete Mária: Pannon tumulus feltárásának előkészítése – Regöly, Strupka-Magyar birtok. Wosinszky Mór Múzeum Évkönyve 36, 2014

Visy Zsolt: A római limes Magyarországon. Corvina kiadó, Budapest 1989.